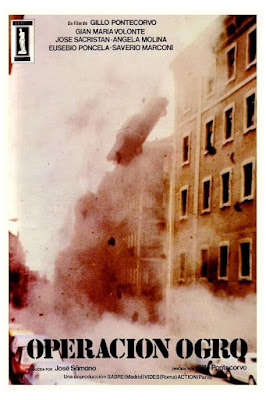

Gillo Pontecovro – former chemistry student, anti-fascist partisan during WW2 and Marxist journalist after the war who was catalysed into filmmaking upon seeing Rossellini’s seminal neorealist work Paisan – is perennially associated with his blazing masterpiece The Battle of Algiers, that remains both landmark political cinema and formally daring exercise. Operación Ogro – his largely overlooked final feature – might’ve lacked in pulsating ferocity, but was no less a cinema of resistance that straddled between rigorous documentation of the eponymous operation and ideological discourse on revolutionary actions, and a compelling political thriller too. Shot in washed-out colours, it’s structured along two interweaving strands, thus covering the divergent routes taken by two comrades-in-arms due to deep dialectical divergences despite their shared love for Basque identity and detestation of Franco; this aspect – and how the death of the one whose choices were underpinned by a more violent method represented the end of a chapter – heavily reminded me of Ken Loach’s powerful IRA film The Wind That Shakes the Barley. The primary track, set in 1973, chronicles in riveting details the mission undertaken by four men and two women belonging to the far-left separatist group ETA – the methodical cell leader Izarra (Gian Maria Volontè), the hot-headed former priest Txabi (Eusebio Poncela), Txabi’s wife (Ángela Molina) and the rest – who relocate to Madrid with the plans of kidnapping Franco’s Deputy PM Carrero Blanco (aka ‘ochre’), but changes that to assassination when he becomes the PM. In the melancholic parallel tract, set few years after Franco’s death, ETA has come to the negotiating table led by Izarra, while Txabi continues to be a radical separatist. The music was scored by Morricone while Ana Torrent featured in a cameo.

Director: Gillo Pontecorvo

Genre: Thriller/Political Thriller/Docufiction/Historical Thriller

Language: Spanish/Basque

Country: Italy/Spain