Kiarostami’s meditation on what it means to be a child in an adult’s world, and in how behavioural dynamics of kids – demonstrable even by something as seemingly ordinary as school homework – are moulded and shaped by both familial contexts and political forces, achieved multi-hued dimensions in this bravura documentary. Furthermore, its nuanced, ironic and disarmingly radical elucidation of the form’s fluidity – achieved through manipulation of the camera’s gaze and inducing of fictive elements that undermine the truth-seeking role that documentaries are expected to play – magnificently presaged his dazzling form-smashing masterpiece Close-Up. It also capped a sublime triptych on pedagogy along with the terrific docu First Graders, which recorded a teacher’s incessant instilling of behavioural traits in a school, and the timeless film Where Is the Friend’s Home?, which portrayed how homework can elicit heroic camaraderie. Influenced by the difficulty that he himself faced while helping his son, he ostensibly formulated this “visual study” and “research project” to comprehend this ubiquitous phenomenon. However, by training his disarmingly equanimous lens on first graders at a working-class boys’ school, he crafted something that transcended the said premise. What emerged through the “interviews” of his adorable subjects is a society driven by punitive culture and fear of reprisals – the kids innately associate “punishment” with belts, aren’t aware of what praise means, and promptly rate their love for doing homework over watching cartoons, even though that’s manifestly untrue – as well as how they’re oftentimes helped by their elder sisters as their parents are either illiterate or too busy or both, and the regrettable seeping in of political narratives even in the “safe” space of schools, as evidenced by references to then ongoing Iraq-Iran War.

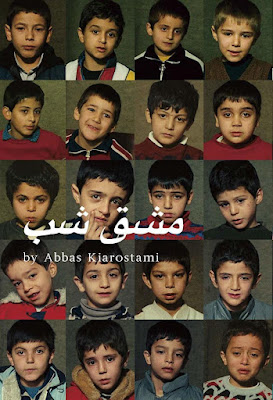

Director: Abbas Kiarostami

Genre: Documentary/Essay Film

Language: Persian

Country: Iran

.jpg)